Are electric vehicles really better for the environment?

Let's look at the lifecycle emissions of vehicles, which include emissions produced when the battery is made, when the vehicle is made, and when the power is made, distributed and consumed.

Discover why moving to electric vehicles is significantly better for the environment, including how EVs in Australia emit considerably less greenhouse gases than internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles, even if charged on the current electricity grid.

Why is this important?

The NRMA supports the reduction of Australia’s emissions through the electrification of our transport sector because EVs can limit ecological damage, reduce smog and improve public health.

Emissions have risen sharply over the past three decades in the transport sector, making up about 20 per cent of total emissions, with light vehicles accounting for about half of that. As motorists, our choices play a key role in reducing these emissions.

Since 2018, the proportion of Australians who would consider buying an EV as their next car has stayed at about 50 per cent, according to annual surveys commissioned by the Electric Vehicle Council and the NRMA. This is not surprising given how environmentally conscious Australians are in their daily lives.

The 2021 Clean Energy Australia report, which provides a comprehensive overview of the Australian clean energy sector, notes that one in four households now have solar panels – the highest rate in the world.

Explore vehicle lifecycle emissions

Explore the chart below to see some common examples of fuel-powered, hybrid or battery electric vehicles and their total lifecycle emissions.

Try clicking the filter to exclude emissions sources. Notice how the carbon emissions from EVs are higher if fuel lifecycle emissions are not included, and how much lower they are compared to ICE vehicles once fuel lifecycle emissions are included – especially when the EV is charged from renewable energy sources like solar.

Read on to find out more about how and why electric vehicles have lower lifecycle emissions.

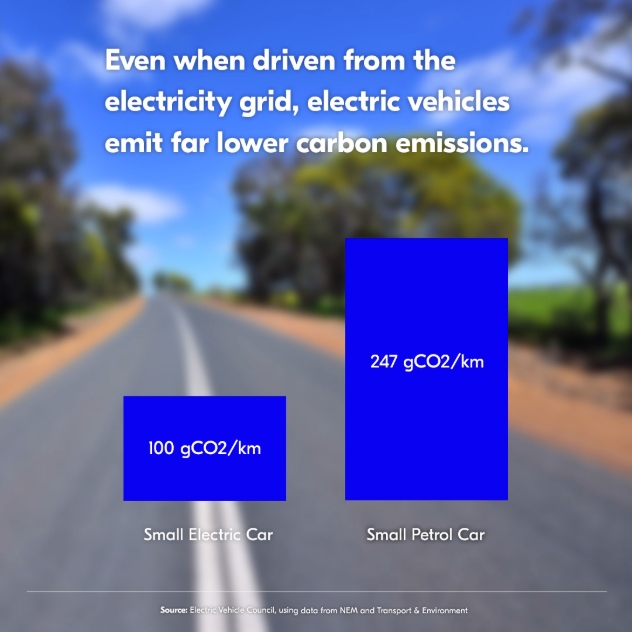

Are EVs better even when powered by coal?

Yes. In Australia, our electricity grid is currently heavily reliant on coal for generation. Despite this, driving a BEV off the current grid is still much less polluting than driving an ICE vehicle.

As the data used in the chart above shows, an average new small petrol 247 gCO2/km over its lifetime compared to an average new small electric which emits around 100 gCO2/km if charged via the grid. As renewable energy represents an increasing proportion of the electricity mix and battery capacity improves, average BEV emissions will fall even further.

p>Plus, there remains the option of charging off-grid; when charged solely via renewable energy sources (e.g. solar), BEVs emit zero emissions.

Do electric cars pollute the air?

No. Unlike ICE vehicles that emit a range of particulates, contaminants, gases and a lot of heat as a result of the combustion process, BEVs only emit a little heat. There are no tailpipe emissions or pollution. Zip. Zero!

However, as with all cars, they use the same compounds in their tyres and these will expel some particles into the environment through normal wear and tear. The same goes for brake pads, although because BEVs have regenerative braking, brake pads generally last longer too.

Are EVs worse to make than cars?

Like ICE cars, EVs use metals, rubbers, plastics and glass in their construction, which contribute similar levels of pollution during manufacture.

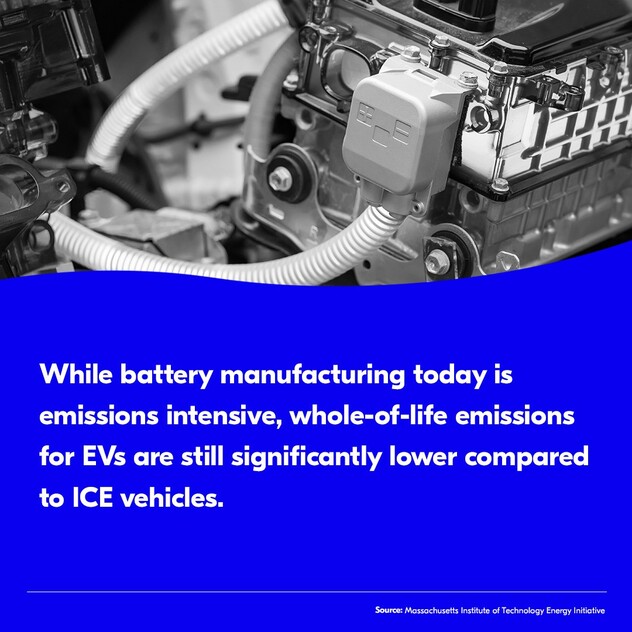

Unlike ICE cars, EVs generally rely on rechargeable lithium-ion batteries to run. The process of making those batteries — from mining raw materials like cobalt and lithium, to production in factories and transportation — is energy-intensive, and one of the biggest sources of carbon emissions from EVs.

Recent studies, including from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Energy Initiative, have found that while whole-of-life emissions (including production) are still significantly lower for EVs, battery manufacture currently dictates that emissions are greater during vehicle production (between 50 and 75 per cent greater for a mid-size, dedicated BEV compared to an equivalent petrol vehicle).

Data in the chart above includes energy consumed in manufacturing processes of raw materials and production of the vehicles themselves, and for vehicles with batteries, the energy used in the extraction of minerals and in battery cell manufacturing.

What about an EV's battery lifecycle?

For end-of-life lithium-ion batteries, reuse recycling is currently possible. Consistent with NRMA policy, leading carmakers and other entities are developing strategic alliances to create a second life market for used EV batteries. Recently, the focus has been on developing large-scale energy storage systems to make use of the capacity that remains in batteries after their use in vehicles.

And there are significant environmentally friendly opportunities ahead. Companies around the world are in a race to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of battery recycling and to craft the next-generation electric vehicle battery that could leapfrog the current lithium-ion battery, improving battery density and efficiency while lessening reliance on rare earth materials.

Data in the chart above assumes the battery will be recycled at the end of its life. Electric vehicle batteries may also be used in second-life capacity for energy storage, which would then further reduce emissions per kilometre as lifecycle emissions are spread over the battery’s extended life.

Can EVs be used for energy storage?

Looking to the future, as more EVs — like the recently reviewed 2021 Nissan Leaf e+— become capable of bidirectional charging (vehicle to grid technology), the opportunity for EVs to become a dynamic, flexible new energy storage source will eventuate.

In this instance, energy service providers could encourage EV owners to charge up from excess, intermittent sources like solar and wind, and then use the energy stored to power their houses when they need it or sell it back to the grid to support grid efficiency and reliability.

Looking forward, electric vehicles can play a positive role in the energy sector and help to put downward pressure on vehicle running costs and electricity prices.

What are other advantages of EVs?

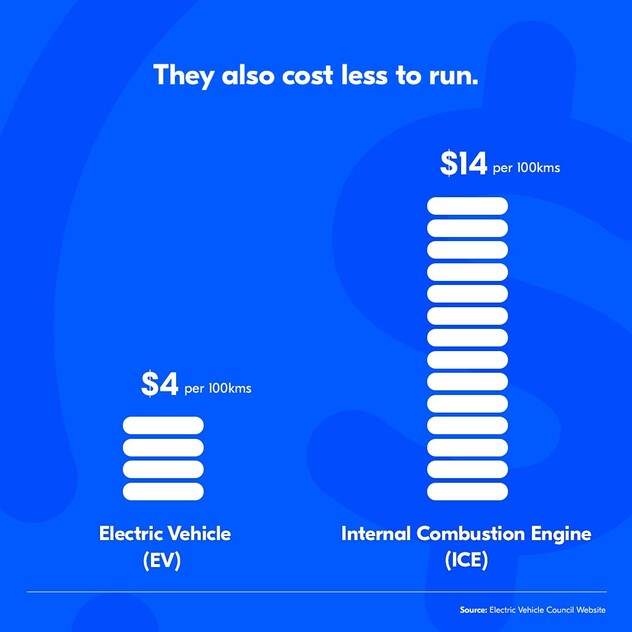

While electric cars are cleaner and more efficient, there are many other reasons for supporting their introduction, including reduced motoring costs for consumers, improved national health standards and bolstered fuel security.

- Lower cost of motoring: The average cost today of running a car on liquid fuel is $14 per 100kms, while the average cost of running an Electric Vehicle is $4 per 100kms – Electric Vehicles also require less maintenance, equating to significant cost benefits.

- Australian fuel security: Producing electricity for vehicle propulsion also has benefits and relies on Australian-made energy, lessening our reliance on importing liquid fuels from overseas markets. While this presents some potential challenges, it also presents some significant opportunities for industry and consumers.

- Economic opportunities: In regard to industry and skills, the NRMA has called for Australia to develop programs to support EVs, their associated components and Australian jobs, including exploring opportunities that may exist with EV battery reuse, recycling and responsible end-of-life retirement practices.

Are EVs better for the environment than ICE vehicles?

In conclusion, BEVs today are significantly better for the environment - even if solely charged via the current electricity grid.

As we continue to improve vehicle technologies and transition towards more renewable energy sources, EVs will become greener. Plus, there are many other potential societal benefits to be realised.

If you are interested in buying an EV, see our tool to determine which EV is best for you.

This article was updated on 23 July, 2024, to include an interactive vehicle lifecycle emissions chart and add updated data comparing the lifecycle emissions of different vehicles.