What are the cheapest cars to run?

The cost of filling up continues to hit drivers in the hip pocket. Fuel prices fluctuated up to 50 cents over the 2023-2024 summer period, and hit a record of 223 cents per litre on the 2024 ANZAC Day weekend. These cycling petrol costs can add up, gouging the household budget significantly.

While internal combustion engine (ICE) drivers scramble to find the cheapest service station, electric vehicle (EV) drivers are now also seeking out the best EV charging deals.

When going to buy a new car, it is helpful to compare potential costs of electric vs ICE vehicles – such as by using NRMA’s fuel versus electricity cost calculator.

Are electric cars cheaper to run?

Without even considering savings in EV maintenance and servicing, the short answer is yes - with some caveats.

For example, the petrol-powered MG ZS costs up to $1958 to run a year based on figures from the Green Vehicle Guide*, whereas the all-electric MG ZS EV costs $743*.

These figures are based on assumptions from the Green Vehicle Guide. Though this uses lab testing data that may differ from real-world driving conditions, it does provide a good comparison of energy/fuel usage and costs between vehicles.

As we outline here, the cost to charge an EV depends on where you are charging and how much energy you need to replenish your battery.

If you are charging at home, the cost of electricity per kilowatt hour is typically less than it is at a public DC fast charger. There are also discounts and sometimes free charging periods offered by energy providers in electricity plans for EV owners.Factors such as how power-hungry your car is, driving conditions and driving style also affect how much you need to charge – just as with fuelling an internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicle.

If charging solely off DC public charging, it is possible for certain EVs to cost more to run than similarly sized hybrids. Another caveat is that different models will be inherently less efficient than others, and EVs typically weigh more because they are carrying li-ion batteries.

For example, the 1-tonne Toyota Yaris hybrid hatchback costs $825 running on petrol for $2/litre and driving 12,500km a year, whereas the 1.6-tonne BYD Dolphin Dynamic electric hatchback costs $975 charged on public DC fast chargers for a year at a rate of 60c/kWh to drive the same distance (see interactive chart below.)

The other caveat is that the cost to run an EV can be even lower if using rooftop solar. Factoring in the cost of solar installations adds another layer of complexity to calculations, depending on household power usage and is not discussed here.

The numbers: How much EVs cost to run compared to hybrid and petrol cars

We compared some popular electric, hybrid and internal combustion engine vehicles, using consumption data from the Green Vehicle Guide.

To compare how much it costs to power an EV to an ICE vehicle, we used the equivalent of litres per 100 kilometres: kilowatt hours per 100 kilometres. We chose a selection of popular vehicles from major segments, using the energy or fuel consumption data from the Green Vehicle Guide for the most efficient and cheapest-to-run variant of each model. See the chart below:

— Bridie Schmidt

How do I work out how much my EV will cost to run?

First you need to know what the energy consumption in kWh/100km of your EV is.

You can find the average city/highway combined energy consumption for your EV on the Green Vehicle Guide. EVs use less energy in traffic than on highways, and use the least power on roads where there is little need for frequent braking and the speed limit is less than for highways (such as rural roads.)

EVs typically show an average energy consumption figure on the display based on recent driving. You can find this in the car’s digital interface, as on this Kia EV6 screen below:

To manually work out how much it would cost to "fill" your battery, use this formula:

EV battery capacity (kWh) x

Price per kilowatt hour ($/kWh) = Charging cost

For example: 60kWh x $0.30/kWh = $18

If you need to estimate the cost for a particular trip you can use this formula:

Energy consumption (kWh/100km) / 100 x Distance (km) x

Price per kilowatt hour ($/kWh) = Charging cost ($)

For example: (15kWh per 100km) / x 100 x 900km x $0.60 per kWh = $81

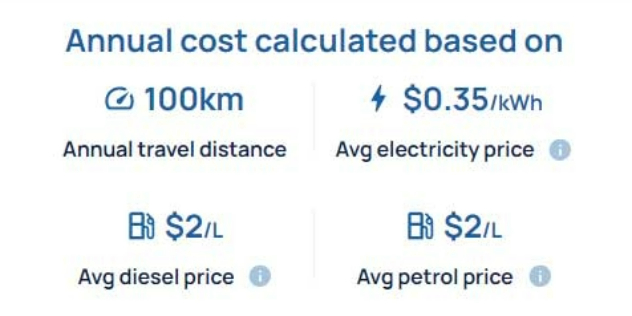

Also, you can work out comparative energy/fuel costs per 100 kilometres using the Vehicle Emissions Star Rating website. Just go to the "Compare vehicles" page and change the “Annual travel distance” to 100km. Choose the vehicles you want to compare and the calculator will give you an estimate based on the NEDC testing data from the Green Vehicle Guide.

If you need to work out EV running costs for tax purposes, the Australian Tax office’s draft compliance guideline PCG 2023/D1 is set at 4.2 cents per kilometre.

Are EVs more efficient than ICE vehicles?

An EV needs less energy to run than an ICE vehicle because electric motors are more efficient at converting energy to motion than combustion engines.

Overall, around 90 per cent of the electricity EVs consume is converted into kinetic energy. More than 70 per cent of the electricity used by EVs goes towards making the car move. This high efficiency is largely because electric motors convert energy directly into motion.

The efficiency of electric motors also remains relatively constant across various speeds and loads, contributing to their overall efficiency in real-world driving conditions.

While EVs do lose some energy through processes like battery recharging, drivetrain losses and power train cooling and steering, their overall efficiency is very high.

Additionally, regenerative braking enhances the energy efficiency of EVs, recouping around 20 per cent of energy back to the system.

ICE cars on the other hand are much less efficient. They convert less than 30 per cent of the energy stored in fuel into mechanical energy. This is because of the complex processes involved in combusting fuel to move pistons to convert the energy into motion.

Energy is also lost through heat, friction, and exhaust. Also, the efficiency of ICE engines varies significantly depending on the engine load and speed, often operating at peak efficiency only within a narrow range of conditions.

What about reports that EVs are more expensive to run than ICE cars?

A recent article tested a BMW 740i against its electric equivalent, a BMW i7 M70. The authors of the article said that on a road trip from Sydney to Melbourne, the i7 cost $15 more for the 900km trip.

The vehicles were (more or less) the same, except for the drive train. But if electric motors are more efficient, why did the EV cost more?

There are a few extra few factors that caused the EV to cost more:

- The battery in the i7 makes it around 600kg heavier. The authors said they did not add a payload to the ICE vehicle to make them equal. This was because that plus the weight of the driver would have taken it over its gross vehicle mass limit;

- EVs use more power at high constant speeds than at low speeds with lots of stopping and starting, whereas ICE vehicles use fuel more efficiently at high constant speeds than at low speeds, with lots of stopping and starting;

The Green Vehicle Guide estimates the annual fuel/power cost of the BMW i7 M70 would be $827 compared to $2,296 for the BMW 740i*.

If the two vehicles were compared on city streets, the test results would have been very different. And, when thinking about how much it costs to power an EV, it makes sense to think about how it is mostly driven.

So, are EVs cheaper to power than petrol and diesel cars?

In conclusion, while the debate over the cost-effectiveness of EVs compared to ICE cars continues, the devil is in the detail.

It's clear that EVs offer a more efficient and often more economical choice for drivers.

Despite higher initial costs and some specific scenarios where EVs may be more expensive to operate, the overall benefits, including lower running costs and less environmental impact, make EVs an increasingly attractive option.

The main things to consider when choosing an EV are what its average energy consumption is, how and where it will be driven, and where and when you plan on charging it.

*Note, although the Green Vehicle Guide uses lab testing data that may differ from real world driving conditions, it does provide a good comparison of energy/fuel usage and costs between vehicles. Actual energy and fuel costs may vary based on individual driving styles, driving conditions and the age and condition of the vehicle.The Green Vehicle Guide advises that, "the estimated annual fuel cost associated with an Electric Vehicle on the Green Vehicle Guide (GVG), energy consumption is declared by the manufacturer in accordance with Australian Design Rule 81/02 (Fuel Consumption Labelling for Light Vehicles), and electricity price data is based on the most recent residential electricity price trends reported by the Australian Energy Market Commission (AEMC)." That is, where the 2021 AEMC report provides estimates, on the GVG this is rounded up to 30c/kWh.