This website uses cookies to improve the user experience. We use cookies in accordance with our NRMA Group Cookie Policy.

This website uses cookies to improve the user experience. We use cookies in accordance with our NRMA Group Cookie Policy.

The purchase price of an electric vehicle is for now still higher than an equivalent internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicle - largely because of the cost of making the battery.

Although manufacturing costs are set to come down as the world transitions to electric vehicles, the sticker price remains a concern for new car buyers.

But it’s worth considering - particularly if you are planning to buy a new car via a loan - that the lower running costs of an EV may offset the higher repayments.

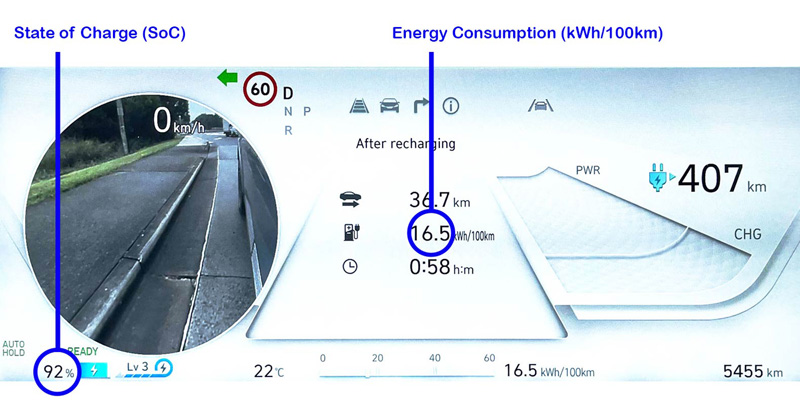

We are used to thinking about “fuel consumption” in terms of litres per 100 kilometres. The EV equivalent is kilowatt hours per 100 kilometres.

Average energy usage for most EVs can range from 120-260kWh/100km, and this can increase depending on external factors such as wind, rain, and hills.

To understand how much power you need per kilometre, find the energy consumption screen in your EV’s interface.

For example, this energy consumption screen below from a Hyundai Ioniq 5 shows it is using 16.5 kilowatt hours per 100 kilometres (kWh/100km.) Some EVs might express this as 165Wh/km.

The cost of charging an electric vehicle depends on how and where it is charged. Instead of paying in dollars per litre, electricity is charged in cents per kilowatt hour.

To calculate charging costs, it helps to know how big your battery is, and what the State of Charge (SoC) is – that is, how “full” it is, from 0 per cent and 100 per cent.

For example, if your EV battery is 50kWh, and it is 40 per cent full, charging it up to 100% will need 30kWh of energy.

Then, it is as simple as multiplying the charging cost by how much energy you need. For example, if a charger is 50 cents per kilowatt hour, the cost to charge to full will be 30kWh x 50c, which equals $15.

How much it costs to charge at home depends on your electricity tariff plan, and whether or not you have rooftop solar.

Some energy providers have specialised electricity plans for EV owners. They include various offerings from rebates on your energy bill, to free or discounted charging between certain hours.

If you have rooftop solar, it is also possible to set your EV up to charge only when there is enough power being generated by your solar system. In this case, the energy is effectively free.

You can reduce your at-home charging costs by using in-built charging schedules or installing a special home charger that starts charging the car when there is excess solar power.

AC “destination” chargers are typically available for public use at locations like shopping centres. Sometimes commercial premises like hotels, motels, pubs or restaurants install them to attract EV owners.

Typically, an AC charger may cost 14-30 cents per kilowatt hour, while AC chargers at commercial premises like motels may be free for the use of guests.

Booking accommodation on a road trip that offers free charging to EV owners can be a handy way of reducing your travel costs.

Note, most AC chargers will require you to have your own cable. Commercial premises may have one you can borrow but it's best to call ahead and check.

DC fast-chargers are the larger units that have thicker heavy cables attached to the unit (this is because the power load is high and the cables must be liquid-cooled).

They charge at a faster rate but you will pay for the convenience as installation and maintenance costs are higher.

Charging at a DC charger typically costs up to 60 cents per kilowatt hour. In some destinations, it can cost up to a $1/kWh, and some network providers offer discounts for motoring association members.

For the latest on NRMA’s national network and rollout of paid EV charging, see here.

Because EVs have far fewer parts than an ICE vehicle, there is much less to maintain and service.

Additionally, EVs use resistance in the motor to recover energy, which slows down the vehicle.

This is called regenerative braking and the offshoot is that there is much less wear and tear on brake pads.

However, there are still items like brake fluid, battery coolant, air conditioning filters and ball joints to inspect or replace, plus tyre replacement costs (leadfoots beware!)

Where they exist, many EV servicing schedules seek to check components for wear and tear. Even so, servicing costs are still generally less than for an ICE equivalent.An example of the difference in servicing costs is the MG ZS and the MG ZS EV. While the ZS costs $1,407 over five years, the ZS EV costs $1,048, as per the manufacturer's recommendation.

The Insurance Council of Australia says that on average, EVs are 18 per cent more expensive to insure. Factors around this include:

Depending on your personal situation, an EV might cost an extra $100-300 a year to insure, adding up to as much as $1,500 over five years.

These costs will come down as demand and then supply for EVs increases. However, in the meantime, expect to pay a premium on electric vehicle insurance.