Indigenous tourism offers unforgettable experiences that give a newfound connection to the diverse landscapes and people across NSW.

The COVID lockdown has been a time of introspection for the tourism industry. Local operators are feeling the pinch of international and interstate travel restrictions but many are finding new and innovative ways to attract domestic visitors.

Indigenous tourism, in particular, offers a uniquely homegrown escape with the potential to have a deep and profound impact on your soul. There’s such a wide range of experiences on offer and the level of luxury, comfort and physical effort is entirely up to you. And with so many different Indigenous nations within NSW, you don’t need to travel far and wide to immerse yourself in rich and diverse cultures.

Wagga Wagga

The town name of Wagga Wagga was previously thought to come from a Wiradjuri word meaning ‘place of many crows’, but in 2019 this was officially corrected to ‘many dances and celebrations’. Here we meet Mark Saddler, an award-winning Wiradjuri tourism operator from Bundyi Cultural Tours. The Macquarie (Wambool), Lachlan (Kalari) and Murrumbidgee (Murrumbidjeri) rivers all border the Wiradjuri lands. Known as the ‘people of three rivers’, the Wiradjuri are the largest Aboriginal nation in Central NSW by area and population.

Mark collects us from our hotel in his luxury seven-seater for a ‘Welcome to Country’. He tells us about the significance of rivers to the Wiradjuri and other Aboriginal histories before painting us in ochre. With fascinating cultural pitstops along the way, we’re whisked up the mountain to Courabyra Wines. Owner Cathy Gairn employs Wiradjuri staff and is proud of the rich Aboriginal heritage of Courabyra, which means ‘pleasant place, family gathering’.

Above: Courabyra Wines owner Cathy Gairn and Bundyi Cultural Tours

We sit down to a menu featuring a ploughman’s lunch, pan seared salmon and wine tastings. You might wonder how it all fits into Aboriginal culture, but the entire time Mark gently regales us with yarns about the Wiradjuri, pointing out significant features in the surrounding landscape. Having never realised that Indigenous language was so onomatopoeic (words imitative of the object they describe), one of the things I most enjoy about Mark’s tour is the way he unpacks language.

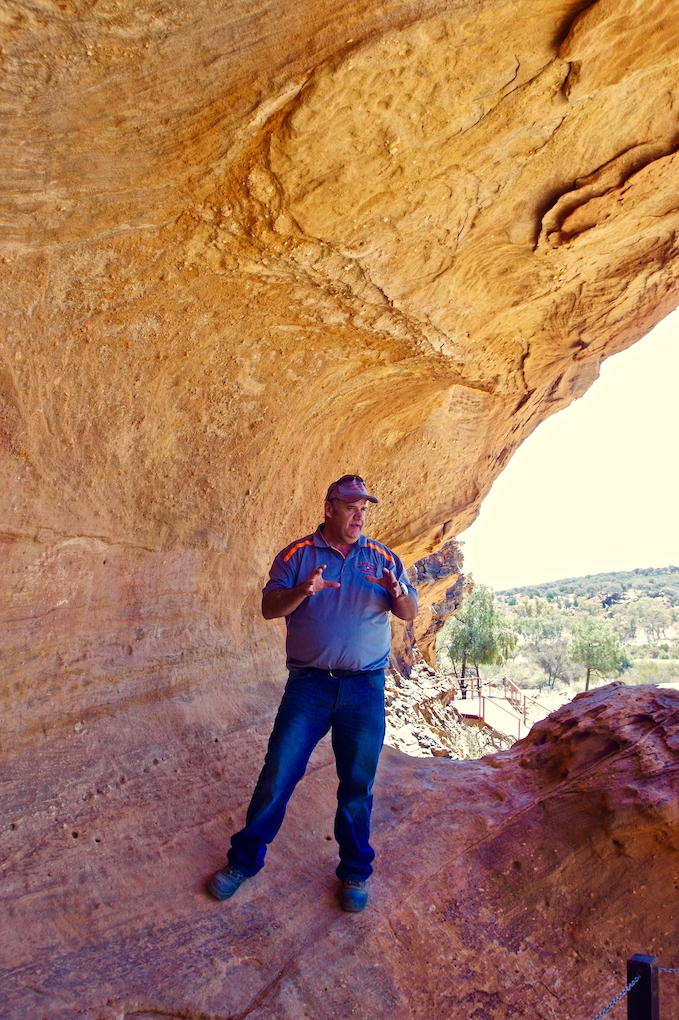

Our next destination is Adelong Falls Gold Mill Ruins (pictured at top of story) where much of the old gold-mining equipment is still intact. I’ve visited this extraordinary site before but enjoy seeing it through a Wiradjuri lens. Unfortunately there’s a lack of signage relating to the Wiradjuri (they earn a lone paragraph). Mark tells us they walked this ngurambang (country) for millennia and are part of the garray (land) here. We listen to Mark’s yarns against the burbling soundtrack of the river and he shows us tools, spears and other items the Wiradjuri used to hunt and gather food.

Chauffeuring us back to the hotel, Mark points to scar trees (bark canoe trees) along the road and dubs Lydia with a totem: Boobook (wise owl). But we agree it’s actually Mark who’s clever, for creating an interesting Indigenous cultural experience that’s easy to dip your toes in.